Jean Luc Godard’s 'La chinoise' is an early example of the political use and production of visual imagery, a strategy which has since become common to many art practices today. The film can be used here a possible case study for the construction of meaningful processes which deals with the concept of censorship, and the conditions in which it is employed.

In a 1976 discussion of Godard’s 'Ici et ailleurs', in "Cahiers du cinéma", Delueze argues that the “and” resists the ontological grounding of the copula to be “neither one thing nor the other, it’s always in between, between two things; it’s the borderline, there’s always a border, a line of flight or flow, only we don’t see it, because it’s the least perceptible of things. And yet it’s along this line of flight that things come to pass, becomings evolve, revolutions take shape.”1 His further readings of Godard’s films, insist on a parallelism between filmmaking and philosophy, in which the “and” or the “border” is a common subject. Delueze sees the typical juxtaposition between a series of screen shots, narratives, images and characters as a new way of thinking, a way that can create an “attentive” spectator in opposition to a passive consumption of the media. Godard plays with a multiplicity of narratives, within which, as theorized by Deleuze, an immanence of time and space is present.

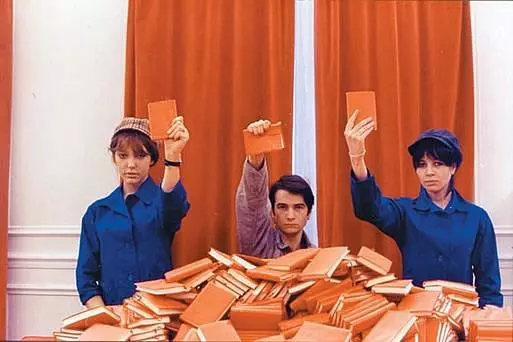

Thus 'La chinoise' (1967) is to be here considered as a political critique of society and the 1968 French student movement. The film is set in Paris and takes place in a small apartment. It is structured as a series of personal and ideological dialogues dramatizing the interactions of five French university students belonging to a radical Maoist group called the "Aden Arabie Cell" (named for the novel, "Aden, Arabie" by Paul Nizan). The five members are Véronique (Anne Wiazemsky), Guillaume (Jean-Pierre Léaud), Yvonne (Juliet Berto), Henri (Michel Semeniako) and Kirilov (Lex de Bruijin), who in their individuality characterize the difficult multifaceted relationship between ideology and reality, the bourgeoisie and the workers movement, the author and authorship.

By working within the film itself, Godard’s montage is a conceptual exposé of the relationship between reality and fiction. Through a series of dialogues, debates, lessons and moments of leisure, Guillaume, Véronique, Yvonne, Henri and Kirilov confront themselves with politics and literature, trying to make the Maoist ideology their own. All the while struggling against doubt, disbelief and the relevance of contradiction in their state of mind. While doing so they isolate themselves from the protests taking place in the streets. To them both Communist China and the war in Vietnam remain afar.

It is within the interstices, the “in-between”, of the image and its construction that the film director reveals the criticalities of, among other issues, the political movement, and gives visibility to those untold moments of doubt and disbelief in what was at stake.

Although Godard does not use original footage of the political protests in 1968, he creates a documentary through fiction. A film which addresses the social issues within the French students movement, while separating itself from imagery of the protests which have taken on an almost iconic stature. Rather Godard is able to antagonize both the movement and the state, to claim a radical form of critically. And it is this position that seems to endure the constant revisionism and reevaluation of 1968.

1. Gilles Deleuze, Negotiations, 1972–1990, trans. Martin Joughin (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), 45.

Share / Save

Share / Save

Comments 4

Say something