AUWH

Artist, Photographer, Journalist, Jakarta, Indonesia, joined 13 years ago

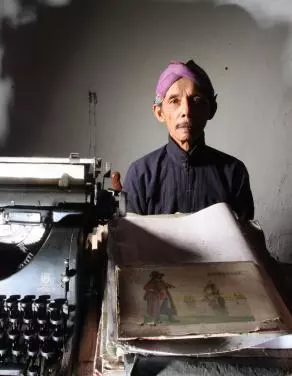

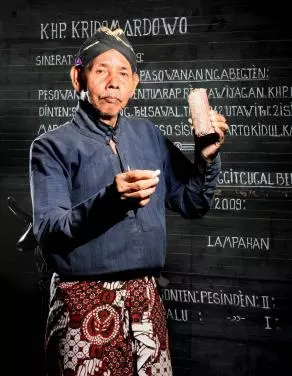

"Servants in the Sultan’s palace, Yogyakarta"

“The lives of the Abdi Dalem in the palace in Yogyakarta form a calm oasis in a world that is more and more driven by material ends.

The Abdi Dalem live a life of service. They do not work for money and for this reason the images do not depict, as it may at first appear, people ‘at work’, but rather the essence of a social identity. Each image contains a rich narrative and bears traces that point to the identity and the life of its subject.”

"The guardians of Javanese tradition"

For more than two and a half centuries, faithful servants in the Sultan’s palace have been safeguarding the Javanese culture in Indonesia. Despite the country’s massive modernisation over the past few decades, there are still over a thousand loyal abdi dalem working on a voluntary basis in the kraton (the sultan’s palace) in Yogyakarta, a small province in Java, Indonesia’s most densely populated island. For them, Indonesia’s new-found democracy is threatening the hierarchical foundations of their language, their thoughts and their service as royal servants.

The special province of Yogyakarta [1] in south central Java is the only province in Indonesia still governed by a pre-colonial monarchy, the Sultanate of Yogyakarta. The city of Yogyakarta is the capital of the province, home to the kraton (the physical and spiritual centre of this old court city) and the centre of Javanese culture, refinement and spiritual power. For the abdi dalem, their spiritual protection and proximity to the sultan, as Allah’s representative on earth, cannot be measured by material standards and even time is measured through the reigning sultan and their service in the kraton.

Inside the palace walls a romanticized past exists alongside the modern, commercialised city a few blocks from the palace gates. When the palace closes for tourists each day, the abdi dalem sprinkle water and flowers on the pillars and burn incense to exorcise evil spirits. They live in a world of whispers and resonant silences full of memories of ancient legends, magic and spirits. For the most part, they are rural poor who serve in the kraton to preserve and absorb the power of this spiritual centre. To dedicate oneself to the work of an abdi dalem is not about finding employment. The calling is based on an inner search for spiritual peace and protection by the divine spirit of the kraton. Their profound and complex faith (based on Islamic concepts influenced by Hinduism, Buddhism and Javanese mysticism) strengthens these custodians of an ancient tradition in their task to safeguard the physical and spiritual properties of the palace and pass on this knowledge and responsibility to younger generations to preserve this cultural centre in Java.

The mystical authority historically vested in the kraton is further reinforced by the fact that it played a leading role during the two most important events in Indonesia’s history. In 1945 Sultan Hamengkubuwana IX was instrumental in Indonesia’s revolution and subsequent independence from Dutch rule. In 1998 his son, Sultan Hamengkubuwana X was a key figure in the democratic revolution which led to President’s Suharto’s resignation and their first free elections in over 44 years.[2]

Like most people in central Java, the abdi dalem speak Javanese, a classical language with an unusually elaborate use of social speech levels. They do not speak Indonesian, the official national language which is based on the more “democratic” Malay language. Deeply influenced by the Javanese culture of knowing your own status in the social order, showing proper respect to those in high positions and protecting those in lower positions, to speak Javanese is to speak in hierarchy as well as in language.[3] The Dutch colonists preferred Indonesian which is less hierarchically structured and much easier than Javanese, as the language of colonialism.[4]

Described by scholars as a form of high art whose inherent graciousness create a world of intense beauty, it is a language of intimate communication, modesty and restraint, which explains the abdi dalem’s passive acceptance of their role as quiet guardians of a spiritual place. With its focus on elegance rather than content, stories are a cooperative effort to create a world of serenity, tolerance and harmony. Speakers will compete to praise and to bestow a calm graciousness on their interlocutors rather than express their own personality and feelings, as the pursuit of personal desires would endanger the harmony. In the early 1990’s, Laine Berman (an American scholar who researched the Javanese language in Yogyakarta) served as an abdi dalem in the palace for two years and wrote: “Sitting cross-legged on the outdoor palace stage without moving for hours (and sometimes all night long) in a tight jarik was agonizing for the first year I served in the palace. In time, however, through the guidance and influence of these old women I learned to deal with and even control the pain in still silence. This lesson, it turned out, was of major symbolic importance for my beginning to understand the Javanese language and its related concept of self.” (Berman 1998:27)

Now, more than ever, the abdi dalem are holding on to their self-repressive values of hierarchy as the foundation for harmony. Yogyakarta is surely one of the few places where given the opportunity to vote for a chief executive, the legislature voted not to vote. However, they cherish their newfound decmocracy and as subject-citizens they now have the right to confirm their Sultan as their governor. (Woodward 2010:8)

For these royal servants, who talk, dream and hope in Javanese, a form of social control in itself, individual freedom is not yet part of their dream.

Share / Save

Share / Save