Gianpaolo Spagnoli

Artist, Verona, Italy, joined 12 years ago

In the course of our existence do we pay attention to small and seemingly insignificant things? How often do we stop to observe and redefine the infinitely small? Spagnoli does it best!

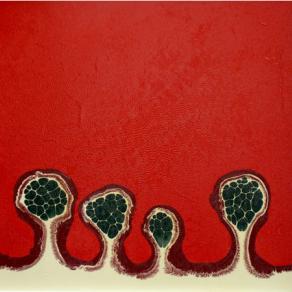

The images of Gianpaolo Spagnoli’s new cosmogony refer to the forms of nature and biology: cells, microbes, viruses and their processes of re-production and fission are the starting point for a research which is not of a scientific-analytic type, but formal and aesthetic. This last term is dealt with in its double meaning: in the current sense of ‘artistic beauty’ and, secondly, in its etymological sense, going back to its Greek origin: ^5;O88;`3;_2;_1;`3;_3;`2;,, where aesthetics is the perception of life through the senses and, as such, in sharp opposition to un-aesthetic: the denial of the sensory field… and, as a consequence, of life itself. And it is just the eternal contradiction between life and death which seems to be the focus of an argument pivoting around microscopic forms, be they good or evil. On the uniform, translucid surfaces, circular, oblong, biomorfic shapes float… inspired by the scientific photos of the mono- and pluri-cellular world. This search has eminent predecessors, joining the path of that biomorfic trend that marked part of the 20th century art of which Wassily Kandinsky is the great father. His abstract shapes drew on music and notes in their vagueness (Spagnoli is also a musician,… a mere coincidence?), creating figures which looked like amoebae enlarged on slides with the help of rudimental microscopes.

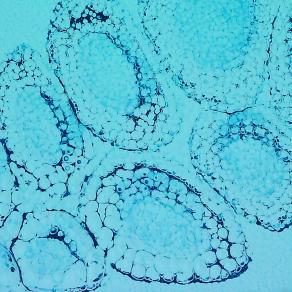

Now, at the beginning of 21st century the perception of reality does no longer pass through these obsolete instruments: on the artist’s vision acts that ‘technological filter’ which by now is at the basis of the picture of our civilization. The images are inspired by digital photos under the microscope, as the title of a series of works on display well illustrates. So, Spagnoli’s search is marked by that ‘overflight altitude’ of Vichian memory, where each phenomenon repeats itself in a temporal spiral but with ever renewed and up-to-date assumptions. Now the artist seems to set his eye on the lens of a powerful technological microscope, fully in tune with our time.

In fact the virtual and digital images are given back to us with such a ‘clarity of vision’, such a hyper-objectivity to make Spagnoli’s paintings sometimes look more photographic than photos, more real than reality itself, as if the artist had launched himself into that science fiction journey described in the film and in the novel ‘Fantastic Voyage’ by Isaac Asimov, where a crew of scientists in a small-scale submarine is injected into the body of Jan Benes.

Likewise, in his works, the artist seems to roam about cells, filaments, tissues, viruses and globules, floating and observing the organism with the same curiosity showed by the crew of the submarine.

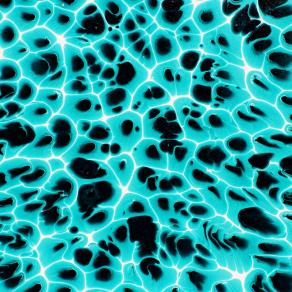

In our wandering about we come across a work with a disturbing title:’Virus’, taking us back, though, to the true core of existence, as if it were reminding us that, behind those biological forms, viruses, hostile to the human race, might be lurking.

After all, the constant warnings resounding against different kinds of flues coming from the four corners of the world, from SARS to Chicken Flu, till the more recent ‘Influenza’ A (H1N1), seem to have brought back the topic of viruses and epidemics, at its apogee during the Middle Ages, and with it the unconscious collective fear paralysing an ever more sterilized and automated world, no longer used to live with (or to succumb to) them.

In fact, in HIV, Spagnoli tackles the delicate question of the new end-of-the-millennium plague, subtly exorcised by the modern cocktails of medicines: this reflection wants to raise a new awareness in us about this illness.

Next to this topic, the artist seems to follow an antithetical path in Mitosis: the process of reproduction by fission of a eukaryote cell generating two identical cells reminds us of the primitive portrayal of life, of vital processes and their intrinsic ‘beauty’.

Chromosome/anthropology instead is an enigmatic and mysterious homage paid to the music of Charlie Parker, a Jazz musician held to be the father of bebop Jazz.

In Gene 1, Gene 2, Gene 3 the titles clearly refer to the presence of three cells with an organic filament whereas in Raptus we witness the collision of two particles which generates a real molecular explosion.

That is how life processes become an aesthetic event to be admired and revised: it is a fact we are prone to leave aside the things we know exist, but we fail to perceive in our daily life.

In CCL (Cell culture laboratory) the effect of cerebral sponginess created by the cells clustering together as if cultivated on the platelet just like a table, where the smoothness of the basis creates a glassy effect; a likewise effect is achieved in Flu-cellphone, whose title is ironic about the excessive use of mobiles and its sanitary implications.

The artistic and formal search, taking biology as its starting point, proceeds along a conceptual path, meditating on the antagonism between life and death and the ever-lasting renewal process taking place in the micro-cell world. These two aspects (life and death) are one next to the other and always interconnected, almost mirror entities in the artist’s vision, almost without any differentiation.

And what stronger contrast could be drawn between the perfection of these viruses, flues, diseases and their lethal connotation for our society? What if the semantic shift implied in this aesthetic interpretation were after all a way to exorcise them all?

News

celeste,