Gianpaolo Spagnoli

Artist, Verona, Italy, joined 12 years ago

Forward, march!

Let us get off the everyday déjà-vu routine to grant us a break among boats, planes, fish, container ships, cans of tuna and maidens left at the mercy of the sea.

The conceptual reflections we find in the last works by Gianpaolo Spagnoli are placed mid-way between the physical reality of things and the boundless semantic openings generated by poetry. A word, this last one – from the Greek ποιέω meaning to invent, to create… that must be taken in the broadest sense of the word – it sounds terribly obsolete in a world dominated by an ever more interactive, interconnected and virtual techno-reality, where Smartphones, Laptops and tablets conquer new areas of our existence becoming part of us, as a kind of new cyber-prostheses the human race is getting addicted to. Despite the undeniable advantages that such an action-reaction system brings with it, a direct consequence of all this is the hyperbolic speed in receiving and elaborating information meant to achieve a Pavlovian reaction in ‘real time’. Such mechanism of immediate feedback is constantly reducing the space for thought, dream, imagination and creativity… to the detriment of the Homo Contemporaneous who is already coming to grips with a growing format-like behavioural homologation. All this implies the loss of that ‘creative surplus’ required for abstraction, which would become unsustainable today both in terms of time and money. To counteract that ‘sellotaped box’, that is today’s life, the only possible way is… to offer alternative emotions, visions, perceptions, thoughts, answers/reactions, be they on the emotional or on the rational level, and that is precisely the theme of Spagnoli’s works: they originate, and not by chance, from a confrontation with Matteo Tonoli’s travel diaries. The idea of travelling as an incessant source of inspiration is present in several works: planes, ships and cars… as if to say that in physical movement resides the opportunity for a poetic estrangement.

The visual-linguistic experimentation shared with Tonoli, the inspiring source for the titles which, in fact, are micro-poems (long meditations in a nutshell) is then rendered by Spagnoli through effective images in the lyrical and amazing Lindbergh (115 x 125 cm.) – referring to the solitary flyer across the oceans, the first to fly from New York to Paris in a reckless (for his times…) enterprise – accomplished with a small scale plane against a glazed blue background.

The reference to the flight as a dream of freedom, as a challenge to new boundaries to cross and new horizons to explore, makes of Lindbergh the most intrinsically poetic work of the whole exhibition.

Moreover Spagnoli’s works do not lend themselves to set values: the correlations between the conceptual images and the micro-poems’ titles bring to life a never-ending process of semantic cross-references as in a game of Chinese boxes.

This same contingent certainty is to be found in What is left of us in the people we have crossed looks with for an instant (75 x 70 cm.) where Spagnoli deals with one of the main pop icons of modernity: the housewife with her shopping trolley.

An icon of modernity, yes, starting from Duane Hanson’s Supermarket Lady (1969), but also an icon of the triviality hidden in our extemporary encounters, in those non-places (non-lieux) – the happy definition is by Marc Augé – where we go in our useless attempt at escaping alienation:

“…a foreigner lost in a country he does not know (q ‘passing stranger’) can only find himself in the anonymity of motorways, service stations, big stores or hotel chains…”

In these ‘new agoras’ (Tonoli), the shopping centres, the emptiness of our crossing looks fully reveals the incommunicability of a life ‘consumed in consuming’.

In our modern industrialized society our leisure time, our diversion and rest is reduced to a production-consumption relationship. Nothing shall remain except for the list of purchased goods and the shadows of depersonalized masses.

Almost at its antipode for her isolation is the miniature of Penelope, a woman sitting on a rock set on a turquoise background, the ideal place for waiting, every dreamer would agree… But, what is she waiting for?

And… are we sure she is really waiting in the first place? Or, more prosaically, is she just enjoying a lazy afternoon totally undisturbed, in peace and tranquillity? Life should always differ, instant by instant, regaining imagination through poetry, its images and suggestions.

The infinite goodness of trees (90 x 85 cm), a miniature of a little man sitting on the ground in the shade of a tree on a glazed green background, despite its sublime light-heartedness, leads to a deep reflection: the book has a close relationship with the tree, being a paper product made from it. Besides, the book is also the inner part of the trunk beneath the bark, where the sap, the nourishment photosynthetized by the leaves, is taken to every part of the tree. The book is the sap, the nourishment of intellect, of circular knowledge, of speculation and abstraction and, ultimately, of the human thought. If in the past the parchment, a very expensive material of animal origin, did not allow the circulation of manuscripts beyond the limits of a restricted group, we owe the spread of culture both to trees and Gutemberg. From such an intrinsically natural material the abstract-scientific thought of our civilization developed.

Once again we find the theme of the book in a small man in the sea, his face up to the sky, all absorbed in reading by a capsized boat… The title, The clouds where we project our dreams (100 x 100 cm) conveys the idea that our thought is a thought in fieri, changing as quickly as we change. After a while the same text assumes emotional connotations with different and unexpected imagery. The pages we browse are just like white clouds passing in the sky… and, as such, they are transitory and ephemeral… exactly like our dreams.

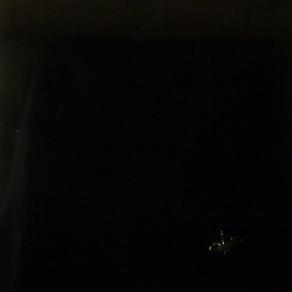

Spagnoli himself gives another very personal interpretation: in the small man all absorbed in reading, one should recognize Tonoli himself for his strong poetic influence. Writing, like poetry after all, is still the focus of his most dramatically intense work: The instant the pen runs out of ink (75 x 75 cm), is portrayed as a bird tangled in a pitch-black glazed bottom.

It is a well played metaphor, taking off from an image highly recognizable by the collective memory; through the media it becomes the symbol of that ‘universal pathos’ which identifies the recent environmental disasters. Despite the efforts of our institutional societies and governments to find a way out through meetings, agreements and sanctions, the possible solution is always remitted to the ink of final declarations taken in summits and shunning a real action which could truly lead to a concrete solution. But when the ink of all those words and efforts runs out, there will be no more room for theory and then…it may be too late. There will be nothing to do after all the black sea of ink has being shed, and this is precisely the moment captured by Spagnoli in this work.

And black is here, undeniably, the colour of a conscious pessimism. Finally, face to face with this unfathomable desperation, the words of prince Myshkin, in ‘The Idiot’ by Dostoevskij, resound as the only possible consolation ‘Beauty will save the world’… through poetry.

Enrico Padovani

Trad.: Raffaella Sala

News

celeste,